Photo credit: Bill Lusk

Here, a prayer I might pray 40 years from now…

Oh, Lord, listen. I am old, my voice hoarse, and our time here is short. It’s Christmas Eve. Before I go, I wish to speak my mind before You and those gathered here.

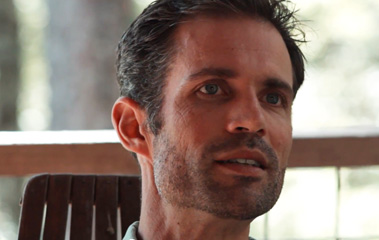

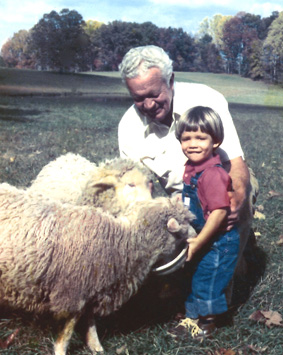

But first, a story: It’s Christmas Eve in Old Salem, 1978. A boy of 5 walks into Home Moravian Church, where he is about to experience his first Lovefeast. He sits with his family in the pew; they sing “Morning Star,” and soon a group of women wearing little doilies on their heads carry in trays of white coffee mugs. The mugs are passed down the pew, and when the boy’s mug finally comes he takes his first sip of the sweet, weak coffee. It will keep him awake for hours, but that doesn’t matter; it’s Christmas Eve, and here come the buns. The boy watches his grandfather put his bun on top of his coffee mug, steam warming its doughy underbelly, and he does the same.

The boy’s family settled long ago in this town of Salem. His great-great-great-grandfather was the bishop of Home Moravian during the Civil War. At the turn of the 19th century, the bishop’s son appeared in National Geographic, his children sitting on giant lily pads growing in their pond on Church Street. But most alive in the boy’s imagination just now is the grandfather who sits quietly beside him, the same gentle man who on Halloween night of 1930 tried to blow up the “Old Moravian Coffee Pot.”

The sculpture stood on the north end of Salem, a 12-foot-high replica of the pots the doily ladies were now using to fill up their white mugs. When the grandfather and his friends dropped a lit bomb down the spout, it failed to destroy the sculpture, only ripping a hole down the seam. Because in making the bomb the grandfather had shellacked together dozens of pieces of his mother’s stationery, the police only had to pick up any piece of confetti littering the scene the next morning to discover a name, an address, and a 16-year-old boy newly amazed at his own power for destruction.

The boy takes his first bite of bread. It’s sweet and moist and has a strange flavor. “Mace,” his grandfather says. The boy is secretly thrilled that he gets to eat and drink real food in church. Yellow beeswax candles with red crepe paper are handed down the pew. The room goes dark. A lone candle is lit, then another, and another, until the light reaches the boy. His lit candle is one of hundreds, and as he holds up his light and munches his bread and sips the sweet, weak coffee, he feels there is no place else he would rather be than here.

The memory of this meal — its peace, its fullness, the knowledge of God’s presence — will follow the boy for the rest of his life. When the boy becomes a man, he will attend a North Carolina seminary, but instead of becoming a preacher he will travel to Mexico to work with Mayan coffee farmers, sharing simple meals of tortillas and sweet, weak coffee. While there he will discern a call from You, perhaps the clearest call you have given him to that point in his life. A call to feed people. The boy-man will go to Chatham County to a small permaculture farm, where he will begin to learn the agrarian arts. He will meet his bride, and together they will help a church start a communal food garden for the hungry — an acre of vegetables and fruit in northern Orange County — and for the next four years the man will lean fully into his calling to feed people.

Such are this old man’s memories. Which brings us to this Christmas Eve. I’ve been thinking about how this faith business you’ve given us really isn’t about doctrine or dogma or even belief. It’s about this hunger we have, and how we fill it.

Hunger is faith’s engine. It’s the driver of all our doings, and it either leads us to Your table of mercy and abundance, or it leads us to fill ourselves with food that does not satisfy. Sometimes I wonder why You gave it to us, this insatiable craving.

“Our hearts are restless until they find rest in Thee,” wrote St. Augustine. But rest implies stasis, stagnation, boredom. God save us from rest. No, our hearts are hungry until they feast on Thee.

Lord, even here in this place we call North Carolina, we still have yet to embody your Beloved Community, where all can sit as equals at the same table. We live in a time of love and destruction, of agape feasts and exploding monuments, of hunger and plenty. May this feast of Your body and blood make us more like You — merciful, kind, open-handed. And if we find the coffee pot of tradition becoming a burden instead of a blessing? Then, Lord, give us the courage to light the fuse of your explosive love, drop it down the spout, and blow the hell out of it.